There are very few translations of Tang poetry out there that have made a real attempt to be poetic - to reproduce the beauty and poetry of the original work, as well as its meaning. So I was very excited to discover Jeanne Larsen this week. Her translations do everything that I want to do with Tang poems, and beautifully.

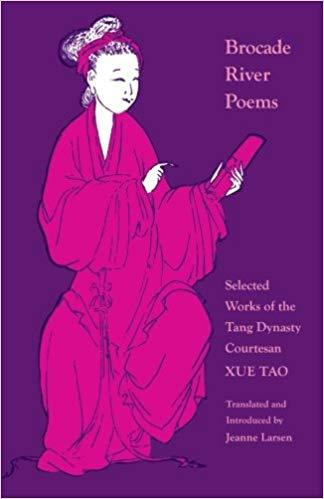

I’m not sure about the ethics of sharing other people’s work that I don’t have the rights to, but I think one short poem counts as fair use. If you get the opportunity, please do purchase her work, though I have to warn you, it’s not that easy to find. This poem is the first in her collection Brocade River Poems: Selected Works of the Tang Dynasty Courtesan Xue Tao.

Poem in Answer to Someone’s "After the Rains, Taking Pleasure among the Bamboo" Xue Tao, tr. Jeanne Larsen When the spring rains come to the southern sky you can just make out— how odd!— the look of frost, the cool allure of snow. The mass of plants mingle thick, indiscriminant, and lush. But this one with her empty heart can hold herself alone. Her groves kept the seven sages high on poetry and wine. Yet earlier still, her tear-splotched leaves grieved with Lord Shun's wives. When your year turns to winter, sir, you will know her worth— her ice-gray green, her virtue: rare, strong nodes. 薛涛 酬人雨后玩竹 南天春雨时,那鉴雪霜姿。 众类亦云茂,虚心宁自持。 多留晋贤醉,早伴舜妃悲。 晚岁君能赏,苍苍劲节奇。

This lovely poem, rather like the Bai Juyi a few days ago, takes a natural image and presents it unobtrusively as a metaphor for human emotion; in this case a woman who has been left, or is not sufficiently appreciated by her lover.

The seven sages of the bamboo grove were a group of writers in the Three Kingdoms period, about 500 years before the Tang, who liked to hang out on bamboo-forested hills.

The spotted bamboo was said to have originated when the widows of the Emperor Shun wept over bamboo and left a pattern with their tears.

Having noticed how great the translation is, I read Larsen’s introduction, and it was almost comical how she thinks about the linguistic issues in exactly the same terms that I do:

“A similar problem arises with the much-discussed freedom of literary Chinese from distinctions between singular and plural (unless they are desired), from verb tense, and even from explicitly stated subjects for some sentences. In the hands of a Du Fu or a Wang Wei these linguistic resources can be manipulated with breath-taking results. But for many Chinese poems, most of Xue Tao’s among them, it seems more “faithful” to the experience of reading the original to look at its context and select an unobtrusive option. Often this context is signaled by the title: a parting poem might just as well be spoken by “I” to “you,” though the more distanced “she” and “he” would also do.”

This talk of ‘linguistic resources’ that poets use to create their effects is exactly the way I approach poems: what did they use, and what did they do with it - and how can I recreate those effects? I feel like I’ve discovered a kindred spirit!

Awesome. Thanks for the recommendation.

Thank you for this lovely intriguing poem. I will try and find this collection.