On a Moonlit Night, I Think About My Younger Brothers Du Fu The army base’s curfew drums cut short My walk. The cry of a single goose above Announces autumn on the border. Dew, From this night on, will turn white. The moon, Out here, is just as bright as once it shone Back home. I have three younger brothers, separated By war. No family remains to ask If they are dead or still alive. I write; the letters never arrive. Most of all, The fighting carries on without respite. 杜甫 月夜忆舍弟 戍鼓断人行,秋边一雁声。 露从今夜白,月是故乡明。 有弟皆分散,无家问死生。 寄书长不达,况乃未休兵。

It’s 759 and the war is still raging. An Lushan rebelled in 756, and took Chang’an. Chang’an was retaken by Tang forces (now under the son of the old emperor) in 757, but outside the capital, the turmoil was far from over. Du Fu was now in the borderlands of Qinzhou, modern Gansu, where the dangers were very real.

This one requires more notes than I usually like to give, because there’s a beautiful flow to it, almost stream-of-consciousness, that I couldn’t give up in the translation. But the first two lines in particular have double meanings that can’t be unpacked while retaining the flow, but won’t be obvious to modern readers. So… notes!

Army base drums: The drums at the base beat out the watches of the night. 3rd watch was curfew for civilians, so Du Fu’s first line is telling us: it’s a moonlit night, and he wanted to spend it outside, looking at the moon and thinking of his family. He stayed out as long as he could, until the drums for 3rd watch told him he had to get home. But the second level of meaning is that the military drums represent the war that is interrupting transport and traffic all across the country. Messengers are not getting through, families have been torn apart.

Single goose: Geese migrate in the autumn, so they represent the changing of the seasons. They also represent mobility, because they can fly from one end of the country to the other; and togetherness, because they migrate in a coordinated flock. When Du Fu hears the cry of a single goose at night, it is undermining those associations. This goose is not together with its flock; and it is crying out in the night because it can’t migrate on its own. This goose means autumn, but also loneliness and disruption.

Moon: The moon is of course the great and deeply ambiguous symbol of family unity. The roundness of the full moon (particularly the September full moon) represents the perfection of the complete family. But when you’re with family, you don’t need to look at the moon. So the moon is the symbol of family that you look at when you’re separated from family. As a poetic symbol, it carries its own negation within itself.

I love the stream of consciousness held neatly within a standard Chinese meter here. The poem starts in medias res, with the poet already looking at the moon and missing his family. The drums intrude on his thoughts, and make him suddenly pay attention to the other things he hears. The goose reminds him of autumn, and the coming frost. The white of the frost links back to the moon, and the moon connects back to home, which makes him think of his brothers. Goose, moon, autumn, frost… these images are the stock in trade of the Tang Dynasty poet, and don’t in themselves carry strongly negative connotations. And yet, using these conventional elements, Du has created a sense of fear, even dread, running through his poem, which is finally made explicit in the very last words of the last line: fighting without respite. It’s a war poem, pretending to be a stream-of-consciousness traveller poem.

Cinix reads these poems in a very understated, businesslike way, and I think it really works for this one.

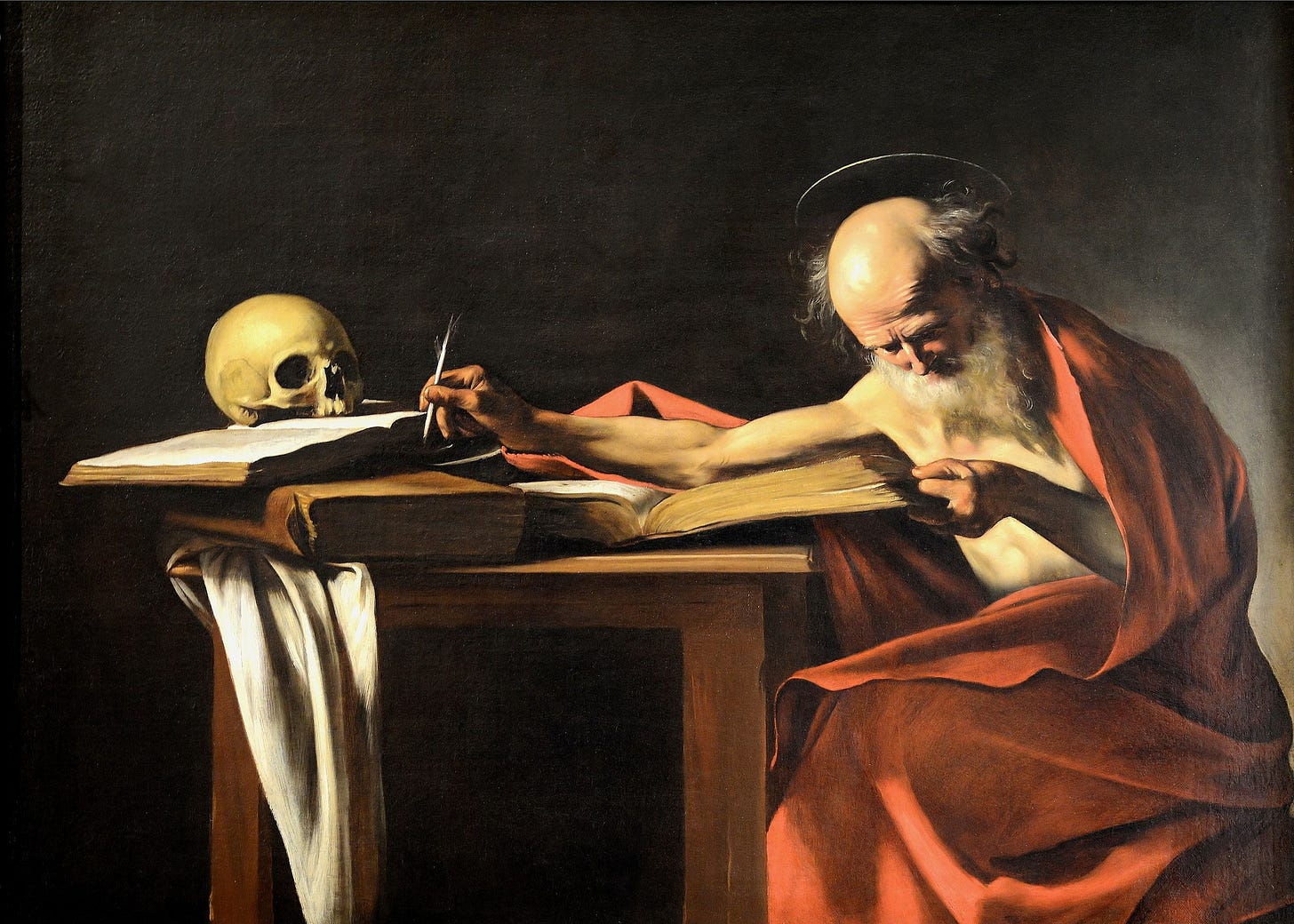

Cross-cultural comparison: The fear in this one made me think of an old Spanish poem that I know through AZ Foreman’s translation: How All Things Warn of Death

Final translator’s note: I love pentameter. The technical difficulties of this poem sent me chasing down a couple of blind alleys (I tried e.e. cummings-style free verse to accentuate the stream of consciousness; I thought about forms like acrostics to hold the theme together while I expanded the meanings). But in the end, the simple flexibility of an iambic pentameter was the only form that gave me anything approaching what this feels like in the source. It’s just a great fit for Chinese short lines.

another good one, mind the lines