Ballad of Changgan (1) Li Bai When I was little and my girlish fringe had just grown out, I used to play and pick the flowers outside my garden gate. A knight appeared, astride a horse he’d made out of bamboo, With unripe plums for marbles, which we chased around the well. Two tiny lives together without artifice or guile, We grew up in Changgan. You were my neighbour, I a child. At thirteen, sir, you came to me as husband, I your wife, A crease of shame was permanently cut between my eyes. I hugged the darkened corners, fixed my face towards the ground, A thousand times you called me but I never turned around. At fourteen, love, my hard expression gradually unfroze, I liked that we’d be blended in our bodies, dust and bones. You promised me no raging tides could keep you from my side, I never kept long vigil like some poor abandoned wife. At fifteen, lover, you departed, sailed so far away, To Qutang Gorge, above the vicious rapids at Yanyu, Too treacherous to navigate in summer after June, While overhead, the skies are full of gibbons’ eerie moans. The scuff marks, where you lingered by the gate when you left home, Have one by one been swallowed up as dark new moss has grown So thick that I can never clear it with my single broom, Now wind and falling leaves have brought the autumn in too soon. September was announced by yellow butterflies which flew Around the evening lawn in Western Garden, two by two. They hurt me, oh, they hurt me, with their dance and flight and play, I sat and feared the bloom of youth on me was turning grey. Sail home through Upper Ba, and Lower Ba, and as you go, Send word ahead to let me know. However far I have to travel, I’ll come to greet my man, As high as I can go upriver, as far as Changfeng Sand. 李白 长干行二首·其一 妾发初覆额,折花门前剧。 郎骑竹马来,绕床弄青梅。 同居长干里,两小无嫌猜。 十四为君妇,羞颜未尝开。 低头向暗壁,千唤不一回。 十五始展眉,愿同尘与灰。 常存抱柱信,岂上望夫台。 十六君远行,瞿塘滟滪堆。 五月不可触,猿声天上哀。 门前迟行迹,一一生绿苔。 苔深不能扫,落叶秋风早。 八月胡蝶来,双飞西园草。 感此伤妾心,坐愁红颜老。 早晚下三巴,预将书报家。 相迎不道远,直至长风沙。

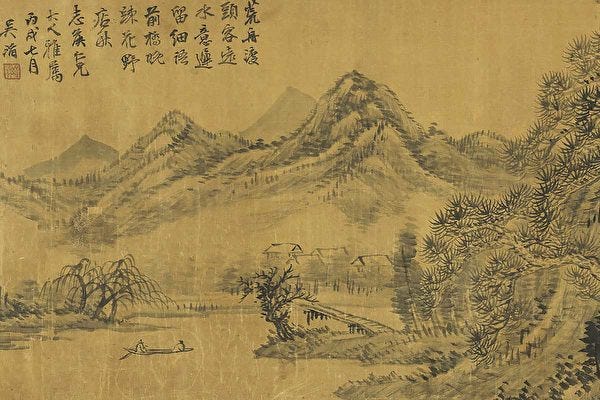

Changgan was a town in what is now Nanjing, on the banks of the lower Yangtze River. The Changgan Ballad was a title used by many poets, invariably writing about lovers who live on the river. Li Bai’s version of this ballad adds the common romantic theme of the wife left alone. But Li’s moving description of the young narrator’s slow acclimatization to marriage is quite unlike most poems, which focus on capturing a single moment.

Fringe: This probably refers to local customs in the hair styles of children. Some sources say girls started to grow fringes at age four, other suggest age ten.

Thirteen: The age of marriage is written in Chinese as 14, but this is using Chinese ages, which are typically higher than age as we now count it. In the Chinese system, a baby is 1 year old at birth, and age increases by one every Chinese New Year.

Raging tides: Refers to a story from the Zhuangzi about a man named Wei Sheng. He arranged to meet his lover under a bridge, but before she arrived, the waters started rising. Rather than risk missing their assignation, Wei Sheng wrapped his arms around a pillar of the bridge, and refused to move until he drowned.

Qutang Gorge: Part of the Three Gorges near modern Chongqing. It’s about 1,000 miles, so a truly vast journey for that time.

Yanyu rocks: Rapids on the downriver side of Qutang Gorge.

Upper Ba, Lower Ba: Counties near to the gorges.

Changfeng Sand: A town in modern Anhui, about 200 miles upriver from Changgan.

This poem actually helps the translator along the way. The place names in the poem other than Changgan are supposed to sound distant and scary to the young narrator, who has never been far from her home town. Their unfamiliarity to the English reader is exactly the right feeling.

For Li Bai’s contemporary readers, these place names struck a deep chord, as well. They were educated servants of the state, always liable to be posted to distant dusty towns at a moment’s notice. Their constant moving created an interest in places journeys that fed through into the poetry of the age.

This poem is a challenge to translate because it is the inspiration for one of the most famous of Ezra Pound’s recreations of Chinese poetry. The River-Merchant’s Wife remains a wonderful piece of work, and very true to Li Bai’s poem in many ways. I’m copying it here simply because it’s always worth rereading.

The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter By Ezra Pound After Li Po While my hair was still cut straight across my forehead I played about the front gate, pulling flowers. You came by on bamboo stilts, playing horse, You walked about my seat, playing with blue plums. And we went on living in the village of Chōkan: Two small people, without dislike or suspicion. At fourteen I married My Lord you. I never laughed, being bashful. Lowering my head, I looked at the wall. Called to, a thousand times, I never looked back. At fifteen I stopped scowling, I desired my dust to be mingled with yours Forever and forever, and forever. Why should I climb the look out? At sixteen you departed You went into far Ku-tō-en, by the river of swirling eddies, And you have been gone five months. The monkeys make sorrowful noise overhead. You dragged your feet when you went out. By the gate now, the moss is grown, the different mosses, Too deep to clear them away! The leaves fall early this autumn, in wind. The paired butterflies are already yellow with August Over the grass in the West garden; They hurt me. I grow older. If you are coming down through the narrows of the river Kiang, Please let me know beforehand, And I will come out to meet you As far as Chō-fū-Sa.